Our schools will improve if they deliver quality arts education to all students. The students deserve nothing less. – James S. Catterall

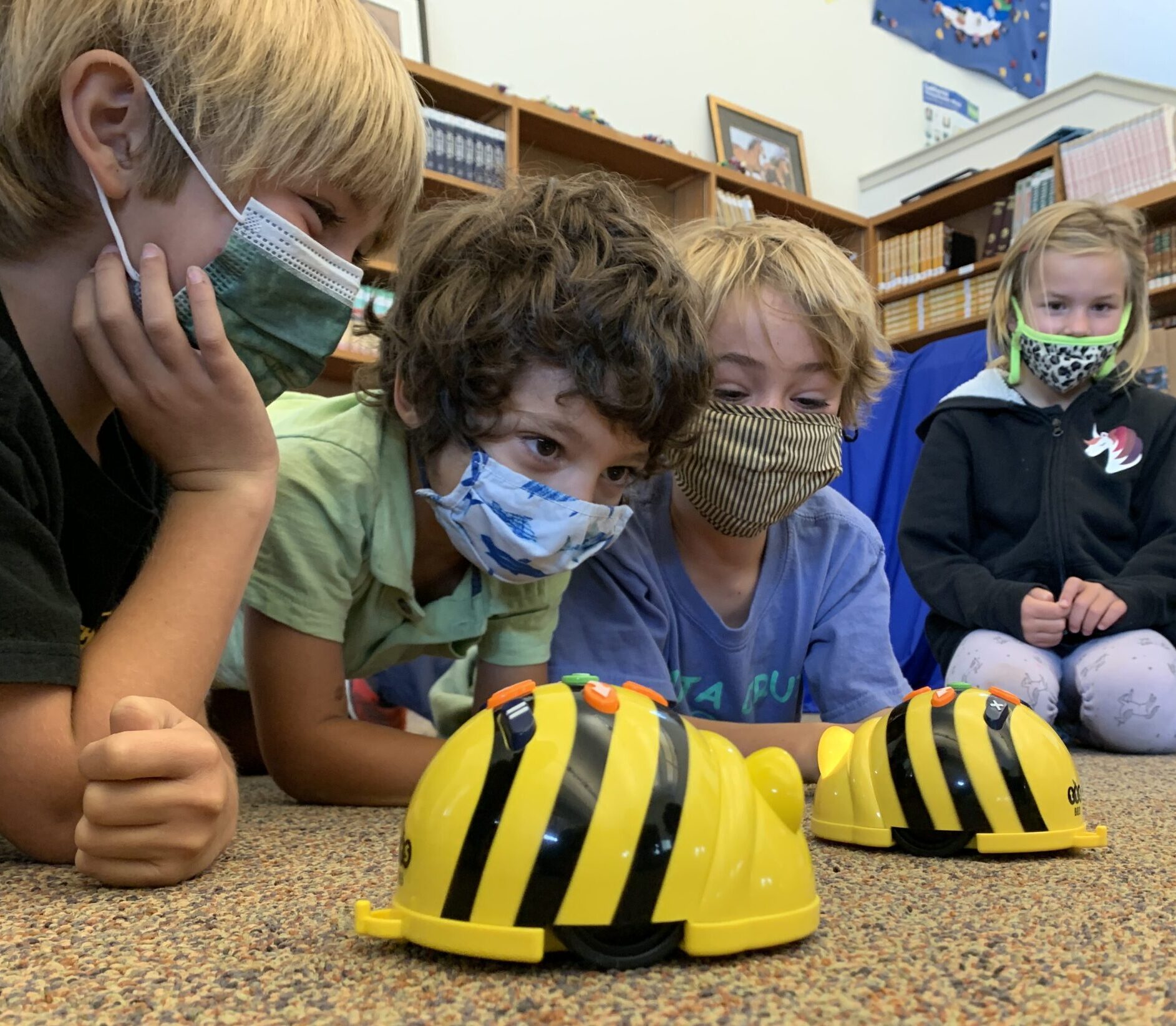

My office just became host to a tray of smiling, blinking robotic bees happily keeping me company as I prepare for my classes. I met my first graders today and their teacher introduced me as their “makers teacher,” and I said, “Oh no, these bees are going to teach you this year.”

They were not yet impressed. I also explained that we were not going to have “makers,” we were going to have “T.E.A. time, which stands for Technology, Engineering, and Art.” Now they were entirely unimpressed. It must have sounded like a mouthful of esoteric nonsense to them. We went around the circle, and I discovered that three of the nine children had already written more than one computer program. I had a group of six-year-olds who were already coding.

I was a little worried, but as we started working with our smiling bee robots, I realized I had a lot to teach them. The bees are designed to teach coding, but they are also good for keeping a classroom of kids joyful as they learn. Even the advanced first grade coders had a lot of debugging to do to solve the problems I gave them and their robot bee (no pun intended). When I mentioned that the bees could hold brush pens and we would be using them to make works of art later, the classroom really started to “buzz.”

I was a little worried, but as we started working with our smiling bee robots, I realized I had a lot to teach them. The bees are designed to teach coding, but they are also good for keeping a classroom of kids joyful as they learn. Even the advanced first grade coders had a lot of debugging to do to solve the problems I gave them and their robot bee (no pun intended). When I mentioned that the bees could hold brush pens and we would be using them to make works of art later, the classroom really started to “buzz.”

Art is a universal human language. Direct connections exist between how much art students learn and their success in all academic subjects and as members of communities. When we teach art, there is technique, or the part that is like teaching any tool for any subject, and there is self-expression, which is something we can encourage and develop. It’s an unfolding for the student, and a process of self-discovery and also one of empathy and compassion. What if students learn different tools and techniques than they traditionally get in an art class, but use those to express themselves, to communicate universally, to create meaning, and to create beauty? If technology, engineering, and art occupy the same spaces in the world ahead of our students, there is great promise and potential in having them occupy the same space in a classroom.

Along the way, of course, it will not hurt that students are solving open-ended problems in infinite ways, collaborating, finding out about how to unearth problems that need solving, innovating, showcasing, iterating, failing and recovering, and learning the creative process. This is the magic and the promise of a program that combines technology, engineering and art.

Along the way, of course, it will not hurt that students are solving open-ended problems in infinite ways, collaborating, finding out about how to unearth problems that need solving, innovating, showcasing, iterating, failing and recovering, and learning the creative process. This is the magic and the promise of a program that combines technology, engineering and art.

On the other end of the age spectrum at our school, I am taking juniors and seniors in high school to Catalina Island. Normally, this is a science trip for younger high school kids, but they missed it during the height of the pandemic. We are building and bringing our own fully operational underwater remotely operated vehicles (ROVs), and we have two weeks to build them. We are creating herbarium-press works of art with watercolors using the incredible ocean plants on the island, and we have a day to learn to do it. When we put this out to the students, asking for volunteers to build and learn, more than half of them flocked to their teachers to give up their lunches and after school hours to do it. I was shocked, then I realized that they want to learn these integrated skills just as much as we want to teach them.

This year, we added a T.E.A. program for grades one through 12. I was shocked by the ease with which this longtime dream of mine became a reality. It was as if last spring, coming back from the most challenging teaching year in recent memory, we all collectively had the courage and the motivation to go out on a limb and try something new. There was no call to simply pour energy into surviving the year, the flexibility the pandemic forced us to have actually held some allure. What if we could flex and try new things and better things, but do it to go beyond for the sake of our students’ future, not to simply make it through COVID?

The ability to solve novel problems is the foremost ability that needs to be fostered in our up-and-coming generations. There is a direct link between asking students to engage in activities that bring multiple disciplines into the same space and students’ ability to synthesize what they have learned into brand new solutions and ideas. Art and science are parallel spaces, and the education needs of this generation pull them together.

The ability to solve novel problems is the foremost ability that needs to be fostered in our up-and-coming generations. There is a direct link between asking students to engage in activities that bring multiple disciplines into the same space and students’ ability to synthesize what they have learned into brand new solutions and ideas. Art and science are parallel spaces, and the education needs of this generation pull them together.

This is the promise of science, technology, engineering, arts and mathematics (STEAM) education. I think the cat is out of the bag for parents that STEAM is a good thing; many parents asking about our school ask if we “teach STEAM.” Many years ago, during President Barack Obama’s second term, the federal government even mandated STEAM and provided funding. At that time, there was no curriculum for it and no way to train anyone to use it. I got an education graduate degree in a cohort of teachers who worked at schools that had changed to “STEAM schools” but had no idea what to do differently.

The truth is, mathematics and science have a canon, standards and a curriculum here that works very well. They are both habits and practices in and of themselves, and I can’t imagine anyone would argue that a good education should not include a treatment of these subjects that is both deep and broad. Teachers of both subjects are well aware of the parallels that exist between learning math and science and visual arts techniques. Picture the posters and sculptures of the inner workings of cells that come home from biology lessons, or the three-dimensional molecules that come out of chemistry units. Art excites students and teachers use it.

Until very recently, the “E” in STEAM, engineering, was something no one really taught in school. The advent of cheap electrical components, 3-D printers, and other technology tools opened up new possibilities and most schools now at least address the subject.

printers, and other technology tools opened up new possibilities and most schools now at least address the subject.

What are the new classes at Mount Madonna?

First-fifth grades: T.E.A., weekly specialist class at the upper campus

Sixth grade: T.E.A., second semester

Seventh Grade: computer science, first semester

Eighth grade: T.E.A., year-long

Ninth grade: T.E.A., year-long, University of California (U.C.)-approved G-category college preparatory course

Tenth grade: Engineering Principles (U.C. honors), first semester, and Oceanographic Engineering elective (U.C. honors), second semester

Eleventh grade: Biomedical Engineering (U.C. honors) or Studio Art, first semester elective choice

Eleventh and twelfth grades, second semester electives (biannual cycle): Computer Science Principles, Advanced Engineering (prerequisite any other engineering course)

Who are the teachers and who started this?

There are four teachers currently working with the T.E.A. program: Angela Willetts, John Walsh, Luis Hernandez and myself. Additionally, Dr. Nicole Tervalon, Ph.D., guided high school Engineering Club students through building underwater remotely operated vehicles (ROVs) for the Catalina trip, and PK McDonald is developing an advanced engineering course for the 2022-23 school year. Together, our backgrounds include degrees and experience in civil engineering, mechanical engineering, art and design, science, oceanographic engineering, electrical engineering, STEAM education and mathematics.

This new program owes a great deal of gratitude to Head of School Ann Goewert, and Upper School Director Shannon Kelly. The origin of this program as a makers program for third through fifth graders, was strongly supported by head of school, Supriya McDonald and the late Jivanti Rutansky, who served MMS in several capacities, including as a co-head of school.

###

Lisa Catterall teaches STEAM, math, science, and art at Mount Madonna School and is a senior associate of the Centers for Research on Creativity. She lectures and trains teachers and administrators on innovation in education in Beijing, China. Lisa has five children and lives in Santa Cruz County.

###

Contact: Leigh Ann Clifton, director of marketing & communications,

Nestled among the redwoods on 375 acres, Mount Madonna School (MMS) is a diverse learning community dedicated to creative, intellectual, and ethical growth. MMS supports its students in becoming caring, self-aware, discerning and articulate individuals; and believe a fulfilling life includes personal accomplishments, meaningful relationships and service to society. The CAIS and WASC accredited program emphasizes academic excellence, creative self-expression and positive character development. Located on Summit Road between Gilroy and Watsonville. Founded in 1979.