On an afternoon in mid-November, Mount Madonna School (MMS) third grade students gathered with their classmates to share their learning about several of the indigenous tribes whose ancestral lands are located throughout California and how they lived long before European immigrants came to the Golden State.

On an afternoon in mid-November, Mount Madonna School (MMS) third grade students gathered with their classmates to share their learning about several of the indigenous tribes whose ancestral lands are located throughout California and how they lived long before European immigrants came to the Golden State.

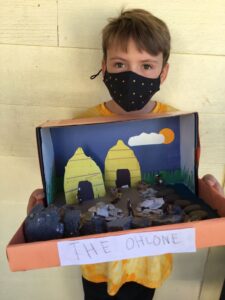

“I learned that I live in Ohlone territory in Aptos, California,” shared third grader Conrad Comartin, who studied the Ohlone people, formerly known as the Costanoan. “When I go to the beach, I think about the people who lived here thousands of years ago. The Ohlone were not wasteful, they put everything to use. Today we should be more like the Ohlone, and not waste so many things.”

In fact much of the greater Monterey Bay region, including inland to San Juan Bautista, Morgan Hill and Gilroy, and the land where Mount Madonna School and its sister organization, Mount Madonna Center, lies on the ancestral lands of the Popeloutchom (Amah Mutsun) and Ohlone people.

In fact much of the greater Monterey Bay region, including inland to San Juan Bautista, Morgan Hill and Gilroy, and the land where Mount Madonna School and its sister organization, Mount Madonna Center, lies on the ancestral lands of the Popeloutchom (Amah Mutsun) and Ohlone people.

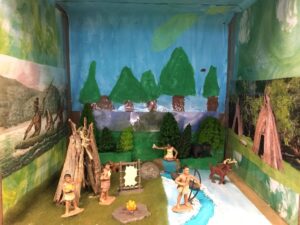

“In third grade, students get the opportunity to study American Indian nations in their local region long ago and in the recent past,” commented teacher Natalie Turner. “They discover and learn things about their tribe’s national identity, religious beliefs, and customs, folklore, geography, climate, and how tribes interacted with new settlers. Students went through the process of gathering information, asking questions, and writing an expository text to share their learning. Students could showcase their learning through creating a diorama, a work of art based on the observation and scenes in their tribe’s daily life.”

Like many of the classes at MMS this year, the third grade has a majority of its students learning in-person, on campus, with other classmates who join the classroom remotely. This successful hybrid program is possible because of the school’s significant technology investment to support its HyFlex learning model.

For their studies, third graders shared information including descriptions of peoples’ diets, housing, social practices and spirituality. Students learned that historically each of these Native American tribes had much larger populations than in current times, occupied vast areas of land, and lived more harmoniously with their surroundings than the settlers who came later.

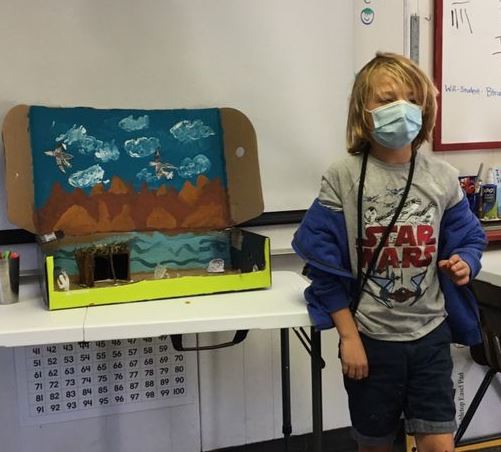

Pippa Mallet, utilizing a home computer and Owl video conferencing technology set up in the classroom, presented on the Wintu tribe, also known as the Patwin or Wintun, who lived in northern California near Mount Shasta and the Trinity and McCloud rivers. Mallet’s diorama had previously been sent up to the school, so her classmates could look it over up close. In the 1700s, some 12,000 Wintu people lived in the area. By 1910, it was estimated only 1,000 remained.

Pippa Mallet, utilizing a home computer and Owl video conferencing technology set up in the classroom, presented on the Wintu tribe, also known as the Patwin or Wintun, who lived in northern California near Mount Shasta and the Trinity and McCloud rivers. Mallet’s diorama had previously been sent up to the school, so her classmates could look it over up close. In the 1700s, some 12,000 Wintu people lived in the area. By 1910, it was estimated only 1,000 remained.

“Wintu means ‘the people,’ shared Mallet. “Their food staples included deer, bear, salmon and acorns. My diorama shows a picture of Mount Shasta, with a salmon on the lake and feathers around it. In the warmer weather they lived in houses that were a circle of sticks tied together at the top. For their winter houses, though, they lived in bigger houses dug below ground with a hole on top for the smoke to get out. One of the most important animals in their stories was the coyote; he was a trickster.”

As the students took turns presenting their reports and listening to one another, they spoke of resourceful people, who hunted, gathered, farmed, created art, traded with other tribes, and at times, went to war to defend their people and homeland. While not every tribe that lived in the California region is federally recognized today, some are, and a few still live on reservations near or on their ancestral lands. Many spoken tribal languages are dying out, though some descendants and tribal elders either remember or still speak their native language.

“The United States signed a treaty in 1864 that recognized and respected the land of the Hupa Tribe,” shared third grader Marc Monclus. “The Hupa tribe is one of very few California tribes not forced from their homeland. According to the 2003 census, the Hoopa Valley Indian Reservation had 3,139 members.”

“The United States signed a treaty in 1864 that recognized and respected the land of the Hupa Tribe,” shared third grader Marc Monclus. “The Hupa tribe is one of very few California tribes not forced from their homeland. According to the 2003 census, the Hoopa Valley Indian Reservation had 3,139 members.”

Monclus studied the Hupa people known as the ‘people of the place where the trails return,’ or the Natinixwe. These people lived in northwestern California, from the southern fork of the Trinity River to the Hoopa Valley, to the Klamath River.

Classmates Will Don Carlos and Narayan Aron-May learned about desert tribes of southern California.

“The Cahuilla people used weapons and tools,” said Don Carlos. “Cahuilla artists are known for their native basket weaving and beaded jewelry. The Cahuilla believed in an unpredictable universe and that their existence came from power. They believed people had different amounts of power which gave them different abilities.”

“The Mojave call themselves ‘the people by the river’,” shared Aron-May. “They lived in brush shelters on stilts near the Colorado River, which flooded seasonally and made it possible for them to farm. They had 22 clans and a chief who the people had to approve. They made pottery, jewelry and weapons out of natural things and traded with coastal tribes. The Mojave valued all dreams and certain people had special roles because of their dream’s meaning.”

Prior to their classroom presentations, the students took a live, virtual field trip to Indian Grinding Rock State Historic Park located in the Sierra Nevadas, to learn about the indigenous Miwok culture and history of the Amador area.

“On our field trip I learned that the park has the largest grinding rock in our country,” said Monclus. “My favorite part was learning about the different arrows they used to hunt different animals. I learned that there is an arrow for ducks that something that floats so that it doesn’t get lost.”

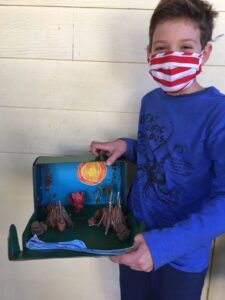

Classmate Dylan Kasznar studied the Maidu tribe of the Sacramento Valley and Sierra Nevada. He shared that at one point the tribe numbered around 10,000 and then fell to several hundred because of the diseases brought to the area by settlers. Today some 2,000 Maidu live in California.

Classmate Dylan Kasznar studied the Maidu tribe of the Sacramento Valley and Sierra Nevada. He shared that at one point the tribe numbered around 10,000 and then fell to several hundred because of the diseases brought to the area by settlers. Today some 2,000 Maidu live in California.

“The Maidu people were masters at building boats out of tule reeds,” shared Kasznar. “One thing I learned that really surprised me, was that the Maidu believed that all people go to heaven, but those who are ‘good,’ get better places.”

Eli Kayne studied the Yokut people of the Central Valley. The Yokuts were unique among the California natives in that they were divided into true tribes. Each had a name, a language, and a territory.

Student Amelie Powers focused on the Miwok.

“The Miwok tribes of the central Sierras also called themselves ‘the people’,” shared Powers. “The coastal Miwok inhabited parts of Marin and southern Sonoma Counties, The Lake Miwok, around Clear Lake. Other Miwok groups lived in the Sierras and eastern parts of central California. They were not wasteful. When they hunted deer, they used all of its parts, including its brain to tan the hide.”

“This student-centered project,” noted Turner, “through active exploration of real-world challenges and problems, allowed students to acquire a deeper knowledge.”

###

Contact: Leigh Ann Clifton, director of marketing and communications,

Nestled among the redwoods on 375 acres, Mount Madonna School (MMS) is a diverse learning community dedicated to creative, intellectual, and ethical growth. MMS supports its students in becoming caring, self-aware, discerning and articulate individuals; and believe a fulfilling life includes personal accomplishments, meaningful relationships and service to society. The CAIS and WASC accredited program emphasizes academic excellence, creative self-expression and positive character development. Located on Summit Road between Gilroy and Watsonville. Founded in 1979.